Ensuring that the poorest and most marginalised can use digital technologies to enhance their learning

)

COVID-19 has taught everyone many lessons, not least in the education sector. However, not all has been negative. Parents have learnt to appreciate just what a fantastic job most teachers do in helping their children to learn, and everyone has come to understand that pandemics and digital tech alike have tended to increase inequalities at all scales. The challenge now is to put such learning to good use, and to help governments across the world use digital tech more wisely in supporting the poorest and most marginalised. COVID-19 is not just a threat, it provides an opportunity for governments to rethink their approaches to the use of digital technology in education.

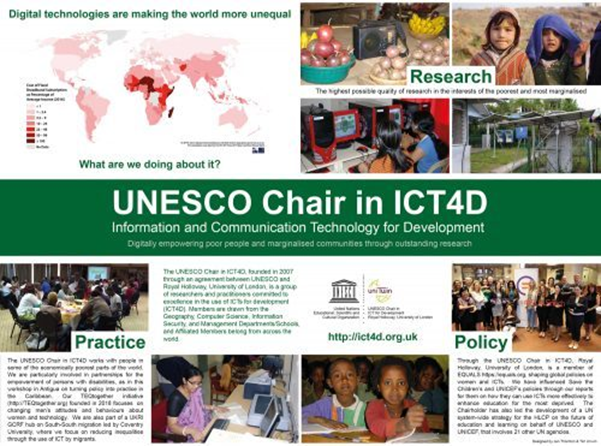

The UNESCO Chair in ICT4D drew on the many years of experience of its members in some of the economically poorest countries to bring together a team of leading academics and practitioners in the summer of 2020 to address just this issue, and craft a new type of report and set of recommendations for governments across the world. This was supported by funding from the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the World Bank through the EdTech Hub, and the active involvement of a panel of leading advisors drawn from government, the private sector and international agencies. At the heart of this work were consultative forums held online with 87 people (43 women and 44 men) from across the world, all of whom provided insights and input into the report’s recommendations.

The outcome was the Education for the most marginalised post-COVID-19: guidance for governments on the use of digital technologies in education report launched in December 2020 and published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 licence. Reflecting a commitment to diversity, partner organisations have helped to translate parts of the report into Arabic, French, Portuguese and Spanish, and some of it is also available as audio files. The report itself is in three Acts, highlighting that it now requires action on the global and national scales. Act One is a short executive summary, crafted for government Ministers and Heads of State, and providing a very clear outline of the most important actions required. Part Two provides the detailed arguments and recommendations of the report. It is designed primarily for the government officials charged with implementing the use of digital technologies in education, but it is also of clear relevance to all those interested in enhancing education for the most marginalised. Part Three consists of 14 short Guidance Notes focusing on the most important specific issues where effective and appropriate interventions using digital technologies can help significantly to increase equity and resilience in education systems. These include topics such as digital technologies and girls’ education, ensuring resilient connectivity, involving marginalised young people in the design of their own education, and inclusion and accessible learning for people with disabilities.

The report begins by emphasising that governments must first make a commitment to create education systems, policies and strategies that address the needs of the poorest and marginalised. It argues that digital technologies often increase inequalities and thus the processes of marginalisation, and a radical alternative approach is therefore necessary if they are to be used effectively to support learning by people with disabilities, refugees, women and girls in patriarchal societies, out of school youth, or those living in isolated rural areas.

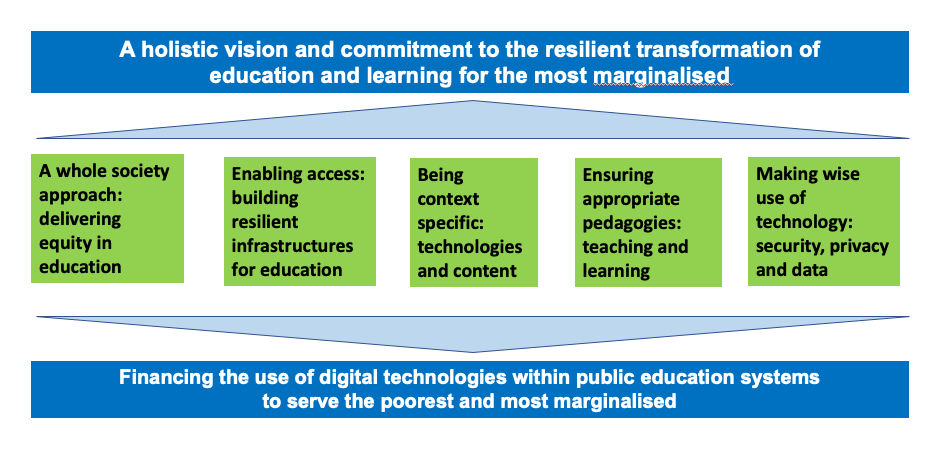

There are then five main things that a government must do once a holistic vision has been crafted that is committed to using digital technologies to create a resilient education system that provides education and learning for all:

- Create a whole society approach that delivers equity in education;

- Enable access for all to digital technologies by providing resilient funded infrastructures for learning, funded by Central Government rather than Ministries of Education;

- Be context specific at all times, especially in terms of the technologies used in education and the content crafted for learners;

- Ensure that appropriate pedagogies are used in the practices of teaching and learning; and

- Use digital technologies wisely and safely.

Above all, it suggests that it is essential to begin by thinking about the educational outcomes that governments and people want to achieve, and only then seek to identify the digital technologies that best suit the context and financial capabilities. Far too often the use of digital tech in education in the past has been driven by other priorities, not least those of the private sector, and this is why it has so often failed to deliver in the interests of the poorest and most marginalised.

These ideas are encapsulated in the diagram below, which highlights in blue the need for this vision and a commitment to equity in financing, lying above and below the five pillars depicted in green.

Some of the most important recommendations of the report under each of these five interconnected pillars can be summarised as follows.

Crafting a whole society approach to making such education happen is not only a means of sharing resources more efficiently and equitably, but it also enhances a stronger sense of community and greater realisation of the need for continuous learning throughout the life-cycle. Within this context, the report focuses especially on:

- the need to involve families, learners and communities in the education system,

- ensuring that effective learning is provided for future employment,

- engaging in productive partnerships with the private sector, and

- creating learning environments that promote wellness and wellbeing.

Access to both connectivity and electricity is essential if any digital technologies are to be used effectively for learning. Without these, it is pointless even considering the use of digital technologies for education. Such access, though, must be resilient, available and affordable for the most marginalised, because otherwise it will only further increasing inequalities. Infrastructures for learning must also be assured for the support of lifelong and lifewide learning, and flexible systems need to be put in place that can be adapted and enhanced so that learning provision may readily be continually improved.

It is also essential for education systems to be context specific in terms of both technologies and content. This means not only that a curriculum needs to be in place to serve the needs of a country and its people, but also that appropriate technologies are used to deliver it. One of the clear lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic is that the use of more or less ubiquitous technologies such as radio and TV remain important and a relatively inexpensive way of delivering learning opportunities for the most marginalised. Moreover, governments must support national strategies for the delivery of high quality, localised and above all relevant digital content that can enable teacher-facilitators and learners to access materials in support of their delivery of the curriculum. Open Education Resources and the use of Creative Commons licences can often usefully support the delivery of these objectives.

Another lesson from COVID-19 has been recognition of the crucial importance that teachers and learning facilitators play in the delivery of effective education systems. Far too often technology is still considered by many in the private sector and government as a means to replace teachers, but it is essential to have appropriate pedagogies in place and teachers well placed to deliver it for a resilient and effective education system to flourish. All those involved in delivering education, from administrators to teachers and assistants must learn how to use a wide range of technologies appropriately and effectively in delivering the curriculum.

The fifth core pillar of the recommendations is that technology should be used wisely in education, especially with respect to security, privacy and data use. Governments must put in place systems, regulations and guidance to mitigate the harms that digital technologies can be used to cause, especially where children and vulnerable adults are concerned. The safety of everyone involved in education and learning must be paramount, and governments should tend towards the precautionary principle in managing educational data.

The report finishes by recommending eight principles with respect to the financing of resilient education systems in the interests of the poorest and most marginalised. These emphasise that wise use of digital technologies need not be expensive, and that harmful and inappropriate uses of such technologies can be both expensive and wasteful. These recommendations include the principle of equity that means that additional funding must be provided for those most in need, that all funding models must be based on the lifetime cost of ownership, that appropriate multi-sector approaches can indeed be a worthwhile means of delivering connectivity and learning to the most marginalised, and that all initiatives intended to go to scale should always be designed at scale.

In conclusion, the report emphasises once again the principle of equity, and also highlights the important principle that all digital learning initiatives must be context specific. It also provides a reminder of two basic pieces of advice about what not to do that all-too-often seem to be forgotten, and yet should always be remembered:

- Don’t put digital technologies into schools without sufficient teachers first being trained in how to use them effectively to enhance learning outcomes; and

- Pilot projects using digital technologies for education should not be done where they are easiest to do and are most likely to succeed, but instead with and amongst the poorest and most marginalised, where the circumstances are most challenging, and where most innovation and creativity is required to make them succeed.

For further information:

- For the full report published in .pdf format: https://edtechhub.org/education-for-the-most-marginalised-post-covid-19/;

- For more background to the report and versions of all three Acts in .docx format, as well as translations and audio: https://ict4d.org.uk/technology-and-education-post-covid-19/;

- For information about the launch including videos from authors, advisory board members and others: https://ict4d.org.uk/technology-and-education-post-covid-19/launch-of-the-education-for-the-most-marginalised-report/

Professor Tim Unwin enjoys working with some of the poorest and most marginalised people in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean (those with disabilities, out of school youth, and women in patriarchal societies) to help them benefit from ICTs. He is also passionately committed to influencing policy through the highest possible quality of our research. His latest book, Reclaiming ICT4D, was published by OUP in 2017, and he is currently undertaking research on sexual harassment through mobile devices, especially in Pakistan, India and the Caribbean. He has recently completed reports with colleagues in the UNESCO Chair in ICT4D for Save the Children and UNICEF on the future of the use of ICTs in education and learning in the most deprived contexts.

Professor Tim Unwin enjoys working with some of the poorest and most marginalised people in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean (those with disabilities, out of school youth, and women in patriarchal societies) to help them benefit from ICTs. He is also passionately committed to influencing policy through the highest possible quality of our research. His latest book, Reclaiming ICT4D, was published by OUP in 2017, and he is currently undertaking research on sexual harassment through mobile devices, especially in Pakistan, India and the Caribbean. He has recently completed reports with colleagues in the UNESCO Chair in ICT4D for Save the Children and UNICEF on the future of the use of ICTs in education and learning in the most deprived contexts.

Natalia Robinson joined UNESCO ICT4D as media relations manager in November 2020. Previously working as a broadcast journalist her focus is centred around raising awareness of environmental and gender issues using different platforms.

Natalia Robinson joined UNESCO ICT4D as media relations manager in November 2020. Previously working as a broadcast journalist her focus is centred around raising awareness of environmental and gender issues using different platforms.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)